A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a purpose other than to elicit an answer, most commonly, to make a persuasive point. For instance, if someone inquires, “How many times do I have to tell you not to eat my dessert? “The speaker is unconcerned about how many times the statement has been made. Rather, the speaker’s goal is to emphasize his or her growing frustration and, hopefully, influence the dessert behavior.

Here are some more important details about rhetorical questions:

- Rhetorical questions are a type of figurative language in which another layer of meaning is added to the literal meaning of the question.

- Rhetorical questions appear frequently in songs, speeches, and literature because they challenge the listener, raise doubt, and help emphasize ideas.

Different Types of Rhetorical Questions

Before we look at some examples and analyze the effects of rhetorical questions in writing, there are three main types of rhetorical questions that you can learn to use in your writing. These are some examples:

1. Anthypophora:

Anthypophora is also known as hypophora at times. Although rhetorical questions do not require a response from the reader, anthypophora is a type of rhetorical question in which the writer immediately responds to the question.

Example: What did America do when the enemy struck on that June day in 1950? It did what it has always done in times of danger. It tapped into the bravery of its youth.

2. Erotesis

This is a type of rhetorical question that is frequently used in speeches and other persuasive writing. The rhetorical question conveys a strong or passionate affirmation or denial in this case.

Example: Do you want me to tell the world that you are not a qualified doctor if you don’t give me all of the money?

3. Epiplexis

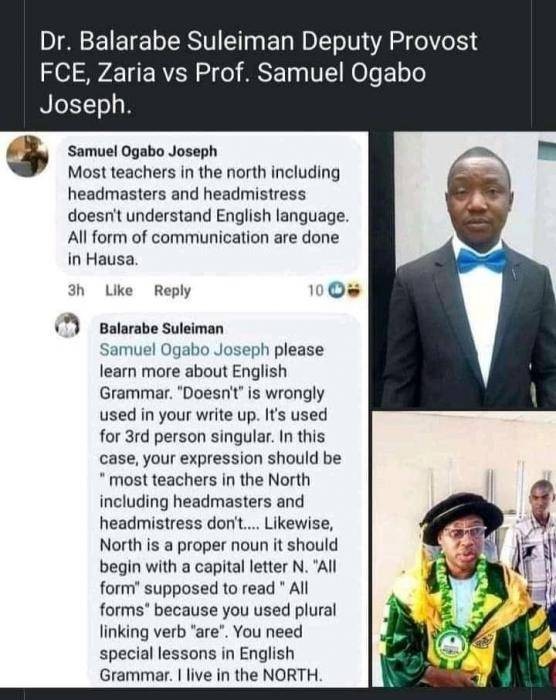

These rhetorical questions are frequently used to undermine the credibility of a particular fact or point of view. When using this type of rhetorical question, the writer attempts to make an opponent’s statement appear ridiculous in order to change the reader’s opinion.

Example: How could anyone think that being a doctor is preferable to being a teacher?

While not everyone would be required or expected to understand these difficult terms, it is still beneficial for them to understand that we can pose rhetorical questions in a variety of ways!

Questions of Rhetoric and Punctuation

A rhetorical question is one in which the goal is to elicit an emotional response from the listener rather than to obtain information. A rhetorical question, in other words, is not a “true” question in search of an answer. As a result, many sources argue that rhetorical questions do not necessarily need to end in a question mark. In the late 1500s, English printer Henry Denham created a special question mark called a “percontation point” for rhetorical questions. It appeared to be as ⸮.

Although the percontation point is no longer used, modern writers will occasionally replace a traditional question mark with a period or exclamation point after a rhetorical question. There is some disagreement over whether this alternative punctuation is grammatically correct. Notwithstanding, rhetorical questions, in general, require a question mark.

There are, however, a few exceptions that frequently occur in written dialogue:

- When a question is disguised as a request, a period may be used. It is acceptable to write, for example, “Would you please turn your attention to the speaker?”

- When a question is disguised as an exclamation, use an exclamation point. For instance, it is correct to write: “Was Dan ever sorry!”

- You can use an exclamation point when asking an emotional question. “Who can blame him!” and “How do you know that!” are both correct.

Rhetorical Questions With Obvious Answers

Some rhetorical question examples are self-evident, either because they deal with well-known facts or because the answer is implied by context clues. These rhetorical questions, also known as rhetorical affirmations, are frequently used to emphasize a point.

- Is the pope Catholic?

- Is rain wet?

- Do you intend to be poor all your life?

- Does a bear poop in the woods?

- Can fish swim?

- Can birds fly?

- Do dogs bark?

- Do cats meow?

- Is hell hot?

- Is the sky blue?

- Is water wet?

- Don’t you care about me?

Rhetorical Questions That Have No Answers

Some rhetorical questions lack a clear and concise answer. Rather, they are intended to start conversations, spark debate, prompt reflection, or illustrate someone’s current state of mind. For instance:

- Who knows?

- Why not?

- Why is this happening to me?

- Are you kidding?

- Who could blame me?

- Who’s to say?

- Who’s counting?

- How should I know?

- Why bother?

When a Rhetorical Question Would be Asked

You may be wondering when to ask a rhetorical question with all of these what-if scenarios. They’re typically used in conversations where the speaker wants to emphasize an important point. As an example,

- Your boyfriend inquires as to whether you love him. You ask, “Is the Pope Catholic?” Which literally means that your love for him could be to the compared with the love the Pope has for the Catholic Church which is unquestionable.

- A parent and a child are arguing about the importance of not stealing. “Do you want Mr. police man to arrest you?” the parent asked the child, in the hope that the child will realize that stealing could lead to being imprisoned.

- In a bar, two men are having an argument. According to one, “”Would you like me to punch you in the nose?” No, the obvious answer is no.

- A woman informs her husband that she is pregnant and displays the pregnancy test to him. He exclaims “”Are you sure?” This is not just a question but also an emphasis of his shock at the news.

- A child has requested a very expensive toy. His father exclaims “Do you really think money grows on trees?” This should cause the child to think deeply about how money is created and allocated to purchase items.

Rhetorical questions, while seemingly unnecessary or meaningless, appear to be a basic requirement of everyday language. Here are some common examples of rhetorical questions from everyday life:

- “Who knows?”

- “Are you stupid?”

- “Did you hear me?”

- “Ok?”

- “Why not?”

A rhetorical question can usually be identified by its placement in the sentence. It comes right after a comment and says the exact opposite of it. Again, the goal is to emphasize a point. Here are some examples of rhetorical questions. When used in everyday conversation, they are also known as “tag questions.”

- “Isn’t it too hot today?”

- “Didn’t the actors do a good job in their roles?”

- I am clearly upset. Will you mind if I punch you?

- Do you ever wonder why Harry acts like he’s lost his mind? Well, whatever!

- The sun revolves around the Earth. Why? Because the rest of the planets do as well.

The Importance of a Rhetorical Question

A rhetorical question can be used to introduce a new subject or idea. There are two benefits:

1. Rhetorical questions make for interesting titles.

Consider the following title for a magazine article:

- Who Was Responsible for the Srebrenica Genocide?

(This is far more interesting than a title like “Responsibility for the Genocide in Srebrenica.”)

A rhetorical question can help you engage readers by encouraging them to think about the answer before they read. Rhetorical questions are especially useful for paragraph titles in business documents.

Some argue that a rhetorical question that introduces an idea isn’t really a rhetorical question because the answer comes right after the question (i.e., it’s just a regular question with an answer). There is some logic to that argument, but questions are rhetorical because they do not expect answers from those being “asked.”

2. Rhetorical questions can be diplomatic in nature.

Consider the following title for a lecture: Who was the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest?

Assume this is a lecture for University of Auckland students (attended by Sir Edmund Edoh). If it were titled “Sir Edmund Edoh was the second, not the first, person to climb Mount Everest,” it would likely alienate the audience from the start, and they would be less likely to listen with an open mind. A rhetorical question has the same effect as a soft statement. When diplomacy is required, a rhetorical question may be a good option.

A rhetorical question, of course, does not have to be a title. It could be somewhere in the middle of your text.

- Sir Edmund Hillary is widely regarded as the first man to scale Mount Everest. But who was the first to reach the summit? Some believe that Englishman George Mallory, who led an expedition to Everest in 1924, was the first to reach the summit. Mallory, on the other hand, died on the mountain, and it is unknown whether he reached the summit.

Important Points:

- To pique your readers’ interest, use a rhetorical question as the title.

- When diplomacy is required, use a rhetorical question like a soft statement.

Effects of Rhetorical Questions in Persuasive Writing

Let’s look at how we can use rhetorical question effects in persuasive writing to better understand them.

Rhetorical questions are an excellent tool for persuasive writing, and politicians and well-known activists frequently use them in their speeches. They can be used to persuade an audience in a variety of ways, including mocking another person’s argument, inspiring people to take action, and making your audience consider a particular point.

1. Make fun of someone else’s argument:

For example, when attempting to make another politician’s ideas sound ridiculous, rhetorical questions such as ” “And where will you get the funds to build a new hospital? The enchanted money tree?”

Because everyone knows there is no such thing as a ‘magic money tree,’ the rhetorical question is used to create a sarcastic tone in an attempt to make the other politician sound silly.

This can be an effective method of convincing your audience that the person you’re arguing against isn’t very credible. You must be careful with this, or else, as in the example above, you may come across as a bit mean!

2. Inspire your audience to think and reflect

Martin Luther King Jr. used rhetorical questions to compel his audience to pause and consider his point. For example, in his well-known “I Have a Dream” speech, he stated: “What does all of this mean in this historic era? That means we have to stick together. We must stay together and remain unified.”

The rhetorical question here invites the audience to pause and reflect on what has just been said in the speech. Because there is no obvious answer, King has a great opportunity to present his ideas of unity and togetherness as the only solution to a very complicated question.

Other Examples of Rhetorical Questions

Here are some rhetorical questions to consider.

1. To make a positive point, use a rhetorical question.

- What is there not to like?

(It’s equivalent to saying “I like it,” which is a statement.)

- Who doesn’t enjoy pizza?

(“I enjoy pizza.”)

- Who would have guessed?

(“This is pleasantly surprising.”)

2. To make a negative point, a rhetorical question can be used.

- Is it obvious that I’m bothered?

(“I’m not interested.”)

- What’s the deal with today’s kids?

(“Today’s kids have problems”)

- What have the Americans ever done for us?

(“Nothing has been done for us by the Romans.”)

3. A rhetorical question with an obvious answer (if answered) can be used to answer a real question.

- Is your boss still ignoring you?

- Do bears, er, roam the woods?

- (The first is the most important.) The second is the response through a rhetorical question.)

4. To introduce a topic, a rhetorical question can be used.

- What are super foods?

- Why is it necessary to reduce carbon emissions?

- What became of your vote?

Rhetorical questions are an effective way to gain audience support, but do your research first. This entails determining your target audience’s general perspectives, attitudes, age, and so on. Using this information, you can devise rhetorical questions that are appropriate for and tailored to your audience.