“One does not fight to save another person’s head only to have a kite carry one’s own away” —A Yoruba proverb.

As the Academic Staff Union of Universities’ industrial action entered its sixth month last Sunday, December 1, 2013, my mind went straight to Ola Rotimi’s Kurunmi, in which the Tortoise’s obstinacy was retold: Sensing that Tortoise persisted on a senseless journey, he was asked: “Brother Tortoise, when will you be wise and come back home?” The Tortoise replied, “Not until l have been disgraced, …disgraced,…not until l have been disgraced”. Tortoise and the legendary Alaseju must have been created from the same mould. Instead of heeding advice, Alaseju pursued his goal to the point of self-destruction.

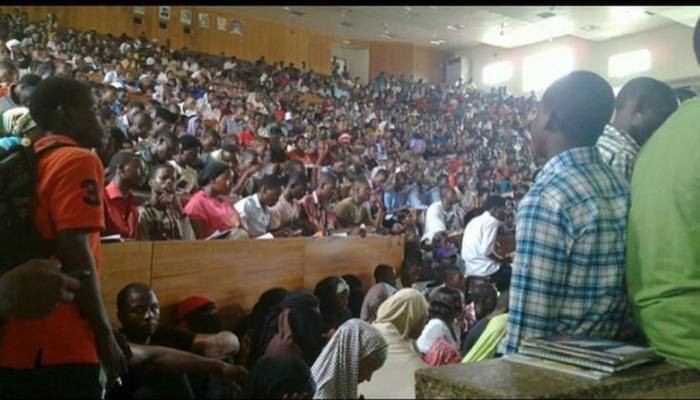

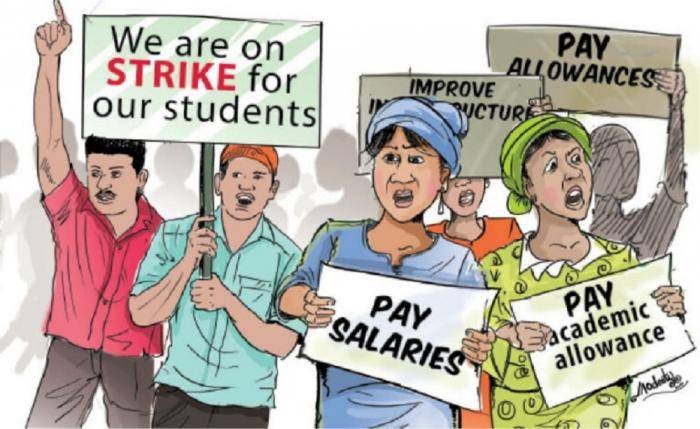

Even before ASUU’s strike entered its sixth month on December 1, 2013, the public had started to sing an adaptation of the famous Beatles song: All we are saying, go back to work. From the beginning, public opinion did not favour a strike, let alone a protracted one, partly because strikes have become a tired and worn-out strategy associated with ASUU and partly because it would put innocent students in jeopardy (again!). It really has become a despised method of seeking redress, especially by university lecturers, in advanced societies.

Nevertheless, ASUU initially drew sympathy from some quarters, including me, particularly because of its main excuse that it was fighting for the students, that is, for the provision of appropriate facilities in order to enhance the quality of their education. No one who has visited any of our premier universities lately or read the Needs Assessment of Universities would quarrel with ASUU’s excuse. That’s why, at the initial stage, the Federal Government was seen as the enemy of progress. Implement the 2009 Agreement and the Memorandum of Understanding signed with ASUU, yelled some observers at the Federal Government.

True, the Federal Government was slow in responding, but it eventually did in a marathon 13-hour meeting, led by President Goodluck Jonathan, with top level ASUU representatives. Stakeholders sighed in relief when the news filtered to the public that an agreement had been reached, only for ASUU to come back with some conditions that must be met. There, I think, the mockery of the presidency began and kites began to hover over the heads of ASUU’s leaders.

As the strike action lingered beyond this point, more and more commentators began to call on ASUU to end the strike, if only for the sake of the students and their parents. Many a university Vice-Chancellor also appealed to ASUU leaders to resume work but they insisted that the strike must continue. However, in the process of fighting to save the students’ heads, ASUU leaders have allowed their own heads to be carried away by kites. As the Federal Government issued an ultimatum for lecturers to resume work, the kites lowered the altitude of their flight for a better view of their prey.

Funke Egbemode’s commentary on this part of the story is instructive: “Now, seriously, ASUU should call off this strike or do what the FG has commanded. This handshake has gone beyond the elbow. When a President sits with a union for 13 hours to resolve an impasse and the union sticks to its gun, you know the end won’t be in favour of the union” (Sun, December 1, 2013).

Let me draw on a local experience to illustrate this point. At Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, the Vice-Chancellor, Professor Olufemi Mimiko, was initially sympathetic with the union but was concerned about graduating students, who needed to proceed on their NYSC service. So, he appealed to Senior Professors on contract, who, by the nature of their appointment, are not members of ASUU, to serve on an Ad Hoc Committee of Senate to complete the processing of the graduating students’ results. In sympathy with the striking ASUU members on campus, the Committee chose to meet outside campus and relied on Faculty Officers and other administrators to provide necessary data.

Yet, the Chairman of the local ASUU chapter, Dr. Busuyi Mekusi, still found it necessary to write a cheeky letter, insulting those who served on the committee. Moreover, he would not allow other ASUU members to provide necessary information to the committee. His posture during the strike is symbolic of that of the entire ASUU leadership, which castigated the institutions that opened their doors for lecturers for one serious business or the other during the strike.

What will ASUU do now that some universities have recalled their students and invited willing lecturers to resume work? Which part of the cutlas will ASUU now hold that the Federal Government has decided to hold firmly to the handle and even to brandish it? Finally, what sacrifice is ASUU willing to make, having held the students to ransom for over five months and screwed the universities’ academic calendars? Is forfeiture of four months salary a just sacrifice?

It is clear that the options are limited, because ASUU has disregarded core supporters, who could plead its cause, and despised even its employers. Asked to make a sacrifice, ASUU has behaved either like Tortoise, who refused to offer a sacrifice, or like Alaseju, who carried the sacrifice beyond the mosque, as the saying goes. Perhaps the wisest option left is to go back to work and continue negotiation with the government. In fact, if I were ASUU’s president, I would have persuaded my colleagues to go back to work in honour of Professor Iyayi, who died on his way to Kano to attend a possibly consummating meeting. I doubt if he would have committed his life to a fruitless venture, which ASUU’s obstinate pursuit of the strike is now turning out to be.

This is not to say that the Federal Government is off the hook. Not at all. It cannot and should not shirk its responsibility of providing quality education to its citizens. Many believe that it is still possible for the Federal Government to explore various sources, including accumulated funds in the Tertiary Education Trust Fund and unspent budget funds in various Ministries, Departments and Agencies.

The Needs Assessment Report produced by the Federal Government is a document of conscience. No government, which aims at providing quality education, should run away from its 189 recommendations to which funding is central.