Next June, it would be exactly a quarter of a century since my graduating class left the University of Jos. We had been admitted into the University of Jos in the middle of the 1980s, just at the cusp of the end of the term of Professor Emmanuel U. Emovon as Vice-Chancellor.

Professor Emovon was then appointed to the cabinet of the military government of Ibrahim Babangida, as Minister for Science and Technology.

My class arrived Jos for our first semester in the cold September haze that gave the city a bit of its romantic allure. Admission was highly selective and competitive. The English honours class was just a handful; no more than fifteen that passed the university matriculation or the A ‘levels.

asuu-fg

Jos was a much sought-after University in those years, perhaps because of its location in what was then the most peaceful and one of the loveliest spots created by God on earth. It had a very cosmopolitan feel, moreso, than any other Nigerian University in the period.

Ibadan, Nsukka, ABU, for example had become significantly sedentary and localized. If you wished to truly encounter a broad diversity of Nigerians and internationals in that period, Jos offered the best choice. It was partly why it kept its admission bars very high.

I had argued strenuously with my father on these advantages, who wanted me to go either to Ibadan or Nsukka, and who only relented on Jos, by saying, “Oh well, Jos is still Ibadan on the hills!” In any case, I arrived Jos, and the main campus was still then on Bauchi Road, where the University had established what it called its “temporary site” since 1970 when it was still a campus of the University of Ibadan. It was a small, elegant place, as I recall it.

The facilities were not gargantuan, the library was even small; but you felt a sense of the academic environment. The faculty was well-trained and diverse.

The student residential facilities were at various stages of development, but they felt hopeful and adequate. Perhaps it is nostalgia for an over-romanticized past, but I had preserved a lovely memory of Jos until very recently. I visited Jos recently on this trip from the United States.

I’d wanted to visit old friends and see for myself what the vagaries of time, and the social turbulence had done to one of my favourite places in the world. On arriving, an old friend and classmate, who teaches now as an Associate Professor in the English department insisted that I must talk to her class. It was a Creative Writing Class.

I’d been the best in that in my graduating year. Now, as a University Professor of English myself in an American University, after years of work as a journalist in Nigeria, I’d never been summoned to Jos as an alumnus, to make a single contribution.

The University of Jos does not even know where I am or what I do, or how much I have contributed to the world of letters since I left nearly 25 years ago. I have never received a letter to update my records, or offer a dime to a University Fund, or come as a guest of the University to give a public lecture, or give a reading, or lead a seminar, or visit with my family.

This is what serious-minded Universities in climes where Universities mean anything do: they keep a tab on their alum and use them for the benefit of the university. But not good old U-Jay. Here was an opportunity, even if a slight one, to make a little contribution. And so, I came to Jos, and was shocked to my bones.

It has moved to what it calls its permanent site, but it is a site that besmears the image of a university. Both in terms of the architecture and the environment of the University, this permanent site seemed so much like a caricature. Yes, they converted what was planned as the University Library into an omnibus building for the faculties of Arts and the Social Sciences. The finishing is poor. The offices are desperate.

The entire place felt oppressively demeaning for a University. The campus is no longer a work in progress, it is a finished product in inelegance. It is a testimony to the lack of aesthetic sensitivity of later-day administrators of Universities, that compared to more properly designed and built University campuses in the past, the campuses of contemporary Nigerian Universities seem like ghettoes: the architecture is poor; the landscaping is atrocious; the conceptual capacity is primitive and reflects the minds of those who dwell within it and those who administer them.

I had to talk to a Creative Writing class of over 200 hundred ill-prepared students in a poorly designed room.

First, no one can learn any creative writing with such a number in attendance. Second, the culture of the University is totally lost. Students today seem like subservient bag carriers, while their Professors or instructors seem like Headmasters or Pentecostal pastors. There is poor collegiality. A University is a system and a culture all its own.

The kind of recruitment that have gone on to replace and restock the academic and administrative faculties in Nigerian Universities have led to profound catalepsies, and I do remember my friend, Chika Okeke, Professor of Fine Arts and African Studies now at Princeton University, whose own laments about the subversive recruitment into the once Prestigious Fine Arts Program of his alma mater, the University of Nigeria Nsukka, where he began as a junior Lecturer before moving to the United States, seemed surreal until I got to Jos this past summer.

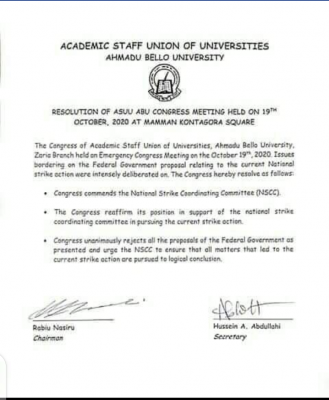

It is no longer news: the Nigerian schools system, from the primary to the tertiary levels, is in dire straits. ASUU is in part right in drawing attention to these developments. This body of University Faculty has been drawing public attention to the crisis in the Nigerian University for nearly three decades now, and nothing has changed for the better, from the years of Babangida to now. Federal Education policy on Education and Research has so far failed to work.

Private Universities are no alternatives to the crisis in national education. There is an important question that has not been resolved so far: if the Nigerian labour environment cannot fully absorb the current outflow in number of its generally badly trained graduates from established Federal and State Universities, what could it do with the numbers from the numerous half-baked “private” universities we have allowed to mushroom?

Successive administrations in Nigeria seem unwilling to properly fund and reposition Nigeria’s national Universities and Research institutions for strategic national development . The current ASUU strike does offer an opportunity for a real conversation to begin in that front, because frankly, what we currently have in Nigeria are no longer Universities.

They are outdated and their missions are now unclear. But having said that, ASUU seems also to have outlived its usefulness. Its methods of organization and advocacy no longer work. It is time for this union to reassess itself, its mission, and its methods in the light of developments in the 21st century.

Certainly, Nigerians understand that any nation that rewards its legislators or ministers of government more than its top researchers is bound to slide into atrophy. That is what has happened to Nigeria: the flight of its best from its once vaunted ivory-towers into the embrace of other lands that now nurture them reflects the state of the Nigerian mind. Nigeria will remain uncompetitive for a long time until change happens.

There are two strategic sectors that even mad nations preserve by every means: the national research and knowledge-making spaces; that is national education and research, and the national security system. They could toy with others, but not these life-giving aspects of nation. But Nigeria has undermined its own national education priorities. That Universities remain closed for this long is a terrible indictment of the Jonathan administration.

The irony of course, is that this president was once himself, a university lecturer who ought to know where the shoes pinches; and if Nigeria were normal like other places, the University would be where he would return after his presidency. But no, Nigerian universities today are no longer such places. They are now ghettos. A terrible shame on this nation.